On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

Episode 20: Grit and Working-Class Solidarity: B.C. Workers Respond to the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike

This episode highlights a remarkable but relatively unknown chapter of working-class solidarity. While waves of sympathy strikes to support the 1919 Winnipeg General Strike took place across Canada, the most pronounced of these was in Vancouver, B.C. Even after workers returned to their jobs, 325 women telephone operators stayed out for another two weeks.

This was a time of unsurpassed working-class consciousness and resistance, the likes of which Canada had not seen before, nor since.

You will hear from Vancouver's legendary firebrand socialist William Pritchard who spent a year in Manitoba's Stoney Mountain Penitentiary for making speeches during the strike.

You'll also hear from seaman Jimmy O'Donnell who arrived in port unaware that a strike was underway, and joined it in the final days, losing his job as a result.

SOURCES:

Bernard, Elaine. "Last Back: Folklore and the Telephone Operators in the 1919 Vancouver General Strike" in Barbara K. Latham and Roberta J. Pazdo, eds., Not Just Pin Money: Selected Essays on the History of Women's Work in British Columbia (Victoria: Camosun College, 1984).

William Pritchard. RG6 Brandon University fonds, Ken Hanly Collection (1974) https://archives.brandonu.ca/en/permalink/descriptions4067

Jimmy O'Donnell. Boag Foundation Tapes, BC Labour Heritage Centre Archives.

MUSIC:

Theme song: "Hold the Fort" (traditional) - Arranged & Performed by Tom Hawken & his band, 1992.

“Strike!” By Danny Schur and Rick Chafe. http://www.strikemusical.com/home/music/ accessed April 2023

"Where the Fraser River Flows" by Joe Hill (1912), performed by Phil Thomas

"Rebel Girl" by Joe Hill (1915), performed by Hazel Dickens

Voice of newspaper editorial: Lucie McNeill

Your affable host: Rod Mickleburgh

Research and writing: Patricia Wejr and Donna Sacuta

Technical wizard: John Mabbott

More Resources:

The 1919 Prince Rupert General Strike

B.C. Sympathy Strikes in 1919

- Follow us https://www.facebook.com/LabourHistoryInBC/

- Browse https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/

- Find us on Bluesky https://bsky.app/profile/bclhc.bsky.social

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bc_lhc/

- Send your feedback info@labourheritagecentre.ca

- Thanks for listening!

Rod Mickleburgh [00:00:05] Welcome to another edition of On the Line, a podcast that brings to life stories from BC's rich labour heritage. I'm your host, Rod Mickleburgh. In our latest episode, we highlight a remarkable but relatively unknown chapter of working class solidarity that took place in this province and across the country. I'm referring to the wave of sympathy strikes to support the renowned Winnipeg general strike in 1919. The most pronounced of these sympathy strikes was in Vancouver. As an added bonus, you will hear from Vancouver's legendary firebrand socialist William Pritchard, who spent a year in Manitoba's Stony Mountain Penitentiary merely for making a few speeches in Winnipeg during the general strike.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:00:58] The first two years after the end of the bloody killing fields of World War I were the most radical in the history of Western Canada. Facing acute inflation and high unemployment, coupled with residual anger over the war, industrial unions across the west tossed aside the moderation of eastern-based craft union organization to demand a six hour day, higher wages, better working conditions and most of all, an end to production for profit. Under the banner of a new movement called the OBU, One Big Union, general strikes were proclaimed as the weapon of choice to achieve their goals. Feelings ran particularly high in BC, where inflation and unemployment were the highest in Canada and employers were resolute in their opposition to union recognition. A record number of strikes swept the province. William Pritchard, son of a British miner and editor of the Socialist Party's "Western Clarion" from 1914 to 1917 was in the forefront of resistance. Interviewed in 1974 at the age of 86 as part of the Ken Hanly collection held in the archives of Brandon University, Pritchard talked about the post-war environment that led to the formation of the OBU.

William Pritchard [00:02:34] Labour was particularly restive, resolution after resolution being passed by various bodies condemning government by Order in Council, the banning of religious, labour and socialist literature, etcetera and returned soldiers developed a more objective and realistic view of the situation. For their wives, for the greater period of the war, had been held to the same meagre allowance that had been first established. Children were kept from school for lack of proper footwear. At one time, a delegation sent by the Trades and Labour Council, of which I was a member, joined with a delegation of returned soldiers and their wives in a visit to City Hall to inform the Mayor of the wretched conditions now facing these men to whom the promise was given that nothing is too good for men who have done what you have done. A surprising thing about this meeting was a fiery speech made by returned soldier's wife. Her voice and manner raised memories of some years previously. And it passed before my mind's eye as clearly as when it happened. It was when I was living in South Vancouver on Maple Street, the house that was raided by the mounted police in 1919, and had to go to work by streetcar. It was in the early morning and I had a seat to myself. Sitting in the seat directly ahead of me were two women who were discussing things rather furiously. I paid little attention until I heard my name mentioned. So I listened with some amusement, but more amazement. I never grew above five feet seven and at that time weighed around 145 pounds. But this man, Pritchard, whose horrible deeds were being so colourfully described at great length, was a monster of some six feet and weighing over 200 pounds. He was, in short, a menace to society and should be summarily dealt with. Now at the City Hall, protesting the wretched conditions of soldiers, wives and children, was the more vociferous of the two ladies of the streetcar ride. When I was called upon to address the Mayor on behalf of the Trades and Labour Council, I gave a short but incisive talk concerning the rapid rise in prices during the course of the war and the absence of any corresponding increase in the allowances to soldiers, wives and families. And contrasted this picture with that of the fortunes made by government contractors. The Sir Joseph Flavelle case, the scandal over the [unclear] contract, the Ross rifle and the defective boots issued to the troops. I received hearty applause from the big gathering. When the meeting concluded, the lady of the fiery speech on the streetcar came rushing over and grabbed me, saying, that was splendid. Splendid. Just a moment, lady, I said. I remember sitting in a streetcar one morning some years ago behind two ladies who were discussing this man Pritchard and describing him in the most derogatory terms. Oh, that. That was some time ago. And we didn't know. Well, I said, it pays to have people know what they are talking about when they begin to talk, doesn't it? Yes, she said rather meekly. But let's forget it. In those early days of 1919, the spirit of rebellion against the government in the ranks of Western Canada's trade unionists was reinforced with opposition to the reactionary policies of the union bureaucracy of Eastern Canada. Resolutions from unions throughout the west poured out in volumes against continued censorship of books, etcetera, against restrictions on right of assembly, free speech, etcetera and many resolutions called for secession from the Labour Congress, dominated by the reactionaries of the East. So overwhelming was this demand that a convention of all affiliated bodies of unionists from the west to coast to the head of the Great Lakes was called to be held in the city of Calgary. The Executive of the BC Federation of Labour decided that for convenience and economy, its convention should be held for the first time outside the province and take place just prior to the Western Conference of Canadian Unions. One thing is significant. The United Mine Workers, for example, were already organized on an industrial basis, and in British Columbia 5000 loggers had been similarly organized. These could not have been organized on any other basis and in any case, no effort had ever been made by the AFL to even approach the question. The first vote taken of the membership showed overwhelming support for the proposed new organization named the OBU.

Music: 'Where the Fraser River Flows' performed by Phil Thomas [00:08:33] Fellow workers pay attention to what I'm going to mention, it is the fixed intention of the Workers of the World. And I hope you'll all be ready, true-hearted, brave and steady, to rally 'round the standard when the red flag is unfurled. Where the Fraser River flows, each fellow worker knows, they have bullied and oppressed us, but still our union grows. So we're going to find a way boys, shorter hours and better pay boys. We're going to win the day boys, where the River Fraser flows.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:09:06] The OBU grew rapidly after its extraordinary founding convention in Calgary. But in Winnipeg, matters had already come to a head even before the OBU got going. From May 15th to June 25th, 1919, more than 30,000 union workers shut down the city as part of an all out drive to force companies to recognize their unions and bargain with them. There's been no event like it in all of North America, and today the Winnipeg General Strike is celebrated in books, plays, songs and even on the screen as a musical.

Exerpt from 'Strike!" by Danny Schur and Rick Chafe [00:09:46] Strike for the hours, how to get what we haven't. Fight to take back the things they took and make right the wrongs... We wont' give up the fight... May 15th, 1919 will go down in history as the day that the workers of Winnipeg, Canada stood united with the workers of the world. We have withdrawn labour from all industry and withdrawn we will stay until the bosses realize that they cannot stand against our masses. No telephone, no telegraph....

Rod Mickleburgh [00:10:44] Less well known is the remarkable outpouring of support for the Winnipeg strikers from other Canadian workers. Sympathy strikes erupted across the country from Victoria and Prince Rupert to the industrial community of Amherst, Nova Scotia. In Vancouver, the Executive of the local Trades and Labour Council was empowered to call a general strike if military intervention took place in Winnipeg. But when Winnipeg postal workers were fired for defying a back to work order, that was enough. Vancouver workers voted to strike on June 3rd to back their striking brothers and sisters in Winnipeg. Labour historian Elaine Bernard argues the Vancouver general strike was even more radical than the strike in Winnipeg because she has written, rather than being directed at local captains of industry, it was motivated by solidarity for workers more than a thousand miles away. And they had their own demands: reinstatement of the Winnipeg postal workers, pensions and compensation for soldiers and their dependents, nationalization of food storage plants to combat post-war hoarding, and the six-hour day for industries hit by unemployment. There are few recordings of those who took part in that long ago strike. But seafarer Jimmy O'Donnell was interviewed by Co-op Radio in the 1970s. Because he had been at sea, he had not joined the strike until its final days. Even then, solidarity remained strong, as seaman O'Donnell relates in his colourful account.

Jimmy O'Donnell [00:12:25] 1919, that Winnipeg strike. When all of Winnipeg was down everybody went out in sympathy. The sailors and the messboys and firemen. So when we come into Vancouver, we brought that scow Spruce down into Vancouver and the skipper says don't go ashore. I says I can't, I gotta go to shore tomorrow. Pickets are all up. I said I got to go to the union hall. I got a report in. I've been out now for nearly a month. So I walked over and the pickets never bothered me. I walked through, had my union button on. Went up to the hall and I says, I just come in. He said where you been? I just just came in, been on the tug Belle. Where's your dues? [unclear] Well, that's the way they treat you, you see. Get your stuff off. Get off, strike on. Okay. I walked down again, that's when -- I worked with this little Cockney guy after that on the Queen City. He come running up to me. He says, what are you doing with that button on? I said, I belong to the Sailors Union. The [unclear] Sailors Union. You know there's a strike on? I said, yeah. He says, where you goin'? I says tug Belle. He said, well there's a strike, you gonna cross this picket line? I said yeah. I'm going down there to get my [unclear]. We just got in last night and I'm gonna take them off the ship. And I'm goin' on strike with you. Two days, the strike was all over. I lost my job.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:13:47] All told, 10,000 Vancouver workers joined the strike. Streetcar drivers, railway workers, woodworkers, stevedores, shipyard workers, brewery employees, city employees, including non-emergency police and firefighters and telephone operators and linemen. They stayed out for an entire month. Union typesetters stayed on the job at Vancouver's three dailies. But when the Vancouver Sun printed a series of strident anti-union editorials, the printers shut the paper down for five days. The Vancouver workers did not go back to their jobs until a week after the end of the Winnipeg General Strike, as they fought to guarantee that those who took part would not be victimized by their employers. And one group of workers remained off the job even longer. 325 women telephone operators stayed on strike for another two weeks in an unsuccessful but valiant attempt to prevent company supervisors, who had also joined the strike, from being fired. They were the last of all Canadian sympathy strikers to return to work. Their noble stand to continue to fight while other unions had called off their general strikes was applauded by Labour's weekly newspaper, the BC Federationist.

Lucie McNeill voicing The Federationist editorial [00:15:12] The action of the telephone girls in responding to the call for a general strike has placed them in a class by themselves amongst women workers in this province. With only a few backsliders, these girls have won the admiration of all those who admire grit and working class solidarity. That their action will be remembered by the workers not only of this city, but by the workers all over the continent, for their loyalty goes without saying. If all the men had displayed the same spirit, the strike could not have been finished, with them carrying on their fight against discrimination after the general strike was called off. The strike was called off as a result of the telephone girls and electricians taking the stand that they could fight the matter of discrimination against the telephone operators alone.

Music: 'Rebel Girl' performed by Hazel Dickens [00:16:15] There are women of many descriptions in this cruel world as everyone knows. Some are living in beautiful mansions and are wearing the finest of clothes. There the blue-blooded queen or the princess, who have charms made of diamonds and pearls. But the only and throughbred lady is the rebel girl. She's a rebel girl, a rebel girl. She's a working class, the strenght of this world. From Maine to Georgia you'll see her fighting for you and for me. Yes, she's there by your side with her courage and pride. She's unequaled anywhere. And I'm proud to fight for freedom with a rebel girl...

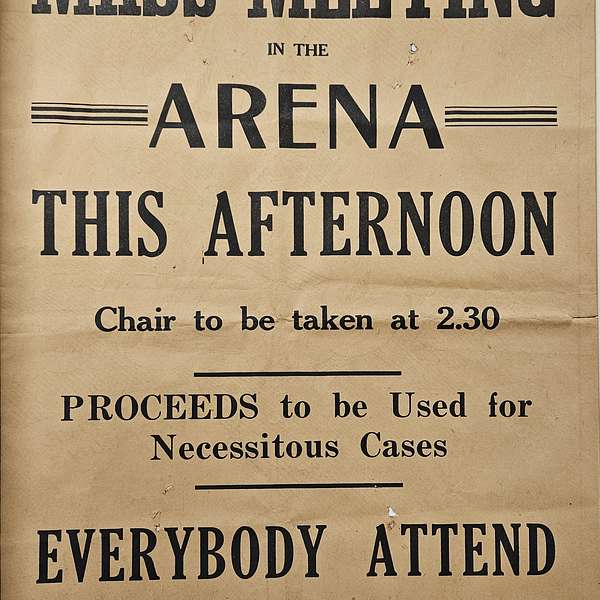

Rod Mickleburgh [00:17:24] The Federationist editorial went on to criticize the decision of other unions not to support the telephone operators by going back to work. Overall, however, the Vancouver sympathy strike was an exceptional event. Despite the widespread use of strike breakers and threats of government sanctioned vigilante action, 45 union locals answered the call. It was a time of unsurpassed working class consciousness and resistance, the likes of which Canada had not seen before or since. And one final note, during the strike, the Native Sons and Squamish Indian lacrosse team, managed by waterfront trade unionist Andy Paul, agreed to play a special match at the old Cambie Street grounds to raise funds in support of the strike. A record crowd turned out, and according to the BC Federationist, "the handsome sum of $65.08 was handed over to the strike relief committee." That, too, was solidarity for the Winnipeg General Strike.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:18:40] And that's it for this edition of On the Line. We hope you enjoyed it. I'm your ever affable host, Rod Mickleburgh. Thanks to the great crew that helped put this together. Patricia Wejr and Donna Sacuta for research and John Mabbott for his production skills. Lucie McNeill read the quote from the BC Federationist. The uplifting songs you heard were 'Where the Fraser River Flows' sung by Phil Thomas and 'Rebel Girl' by the great Hazel Dickens. Both songs were written by the legendary Joe Hill. We'll see you next time, On the Line.

Theme music: 'Hold the Fort' [00:19:17]