On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

Episode 15: Smelter Wars

The workers at the lead-zinc smelter in Trail, British Columbia have a long history of overcoming formidable obstacles to unionization. Contentious politics, a company union and two World Wars are some of the issues discussed in this episode.

We talk to Ron Verzuh whose new book Smelter Wars: A Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for its Life in Wartime Western Canada (University of Toronto Press, 2022) has just been published. We also listen to archived interviews with two men who worked in the smelter in the early 1900s and remembered Ginger Goodwin who led a strike there in 1917.

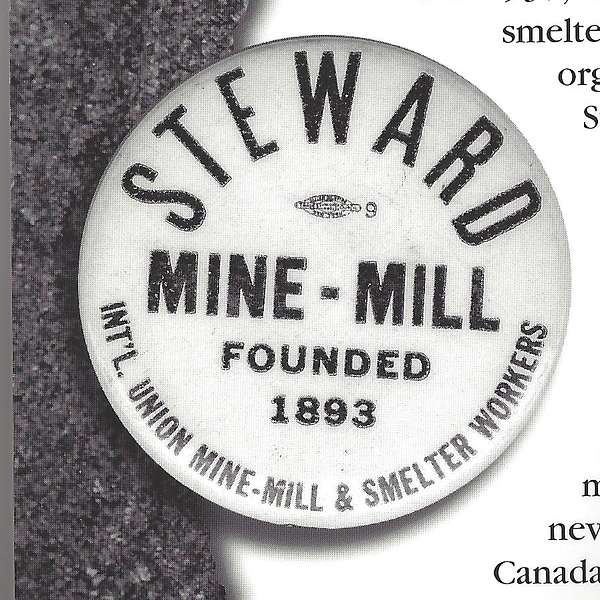

Originally members of the Western Federation of Miners, who became the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers, the workers at the Trail Smelter (Cominco) are now represented by United Steelworkers Local 480.

FEATURED MUSIC: Theme song: "Hold the Fort" - Arranged & Performed by Tom Hawken & his band, 1992. Part of the "On to Ottawa" film produced by Sara Diamond.

“Ode to the Union Smelterman” (1907), author unknown. Performed by Jeff Burrows.

RESEARCH: Research and script for this episode by Patricia Wejr & Rod Mickleburgh. Production by John Mabbott.

Andrew Waldie interview, RECORDED: 1975-12-18 by Howie Smith. ©Royal BC Museum

Ed Provost interview, RECORDED: 1975-12-20 by Howie Smith. ©Royal BC Museum

Cominco History – Rossland Museum & Discovery Centre retrieved at https://www.rosslandmuseum.ca/cominco

- Follow us https://www.facebook.com/LabourHistoryInBC/

- Browse https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/

- Find us on Bluesky https://bsky.app/profile/bclhc.bsky.social

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bc_lhc/

- Send your feedback info@labourheritagecentre.ca

- Thanks for listening!

Rod Mickleburgh [00:00:19] Welcome to another edition of On the Line, an original podcast that shines a light on BC's rich labour heritage. I'm your host, Rod Mickleburgh. Today we visit the West Kootenay city of Trail and examine the long, colourful history of union organizing and its large and storied smelter. The first smelter was built at Trail Creek Landing way back in 1896 by a young entrepreneur named Frederick Augustus Heinze, so the rich ore mined in nearby Rosslyn could be processed locally. Over the years, it grew into the largest smelter complex of its kind in the world, producing refined lead and zinc, a variety of speciality metals, chemicals and fertilizers. But as usual, in those early days, the workers who actually produced the wealth toiled long hours for low pay and terribly hazardous conditions. Most were immigrants, including my grandfather, recently arrived from Finland, who worked at the smelter for nine months in 1929 until he was fired. Not surprisingly, the large, exploited workforce was ripe for organizing. Those efforts were contentious and the politics formidable. Company unions versus legitimate unions, communist union leaders versus anti-communist union leaders, egged on by the church and the local newspaper. International unions versus Canadian organizations. Toss in a key chapter of the life of labour martyr Ginger Goodwin, and you have quite a story. There is now a new book to pilot us through all the drama. Historian Ron Verzuh was born in Trail and worked briefly in the smelter as a young man. His well-researched book, 'Smelter Wars: a Rebellious Red Trade Union Fights for Its Life in Western Canada', has just been published. He spoke recently with Patricia Wejr. The interview takes up much of this podcast, but we will also hear from two men who started working for the Consolidated Mining and Smelter Company in the early 1900s. Ed Provost and Andrew Waldie were interviewed by Howie Smith in 1975. Along the way, you will also hear verses of 'Ode to the Smeltermen', a song from 1907 unearthed by Ron Verzuh and performed for On the Line by Jeff Burrows. We begin with Ron talking about why he wrote 'Smelter Wars'.

Ron Verzuh [00:03:11] For starters, I'm from that area. I was born in Trail and grew up in that area. And so part of this was kind of just curious about my past and about my family's past. Many of them worked for the smelter, including my mum, as a secretary. So I sort of took a historian's view of it, but I also took a personal view. What happened back then, what did my parents lived through? What did their parents live through? Because my grandfather worked for the smelter as well. So I had that kind of personal side of it, but I was also very curious. I was curious politically because I'm from the left. I've been from the left for my whole life. And I worked in a situation where I saw a lefty union and basically supporting the workforce in Trail when I worked there in the '60s. So some of these things coalesced into a real interest in what happened for these interesting 15 years or so where they were building the union and they were running into the -- they were confronted with all sorts of institutional argument that they shouldn't be allowed. And of course, there was the left-right argument of communism versus the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation versus the employer versus the churches and so forth. So it just became a kind of interesting personal study. But I had historians credentials, so I was able to use some of those tools to pull the story together.

Patricia Wejr [00:04:35] Could you tell us a little bit about the work that you did at the smelter in the '60s?

Ron Verzuh [00:04:40] Oh, goodness. I started out at 18 years old in a place called the phosphate plant. And there were two sort of Siberias at Cominco, as we were calling it then, and one was the phosphate plant, which is a fertilizer plant, and it has all sorts of acid tanks and terrible big grizzlies churning around with rocks in them. That was the first experience. The second experience was in the other hell hole, which is called the lead furnaces, and that was down below in Tadanac. The smelters divided up into Warfield's plants and then Tadanac's plants as it's described in the book. And that was terrible because we were facing pretty much danger all the time because they had lead in the air and you would breathe, you were breathing in lead. And basically a lot of people got what they call leaded or lead poisoned and died. Not to mention other things, asbestosis and other lung diseases. So it was a pretty dangerous spot. I was in there for about a year or so and didn't get leaded, but I'm glad I got out when I did.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:05:52] Ron added that conditions are likely much better today than 50 years ago, thanks to ongoing union health and safety campaigns.

Music: 'Ode to the Smeltermen' performed by Jeff Burrows [00:06:01] You work in heat and gaseous fumes from day to day you strive, to feed and furnace tap coal pots like bees around the hive. And wheeling charges, crushing ore then sampling bullion too, 'til all begrined with dust and sweat, quite languid you get through. So smoke and drink like brothers who let not your minds provoke and practice strict equality while you toil in smelter smoke.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:06:48] Ed Provost came to Trail in 1912. He worked as an electrician at the smelter until his retirement in 1952. He was still living in Trail when Howie Smith talked to him in the mid-1970s. When he began, said Ed, they worked seven days a week, no days off and other working conditions:

Ed Provost [00:07:10] Well, to what they are now, they were bad. [laughing]

Howie Smith [00:07:17] Give me some examples.

Ed Provost [00:07:21] [laughing] Well, you never had any washrooms and nothing. You'd eat your lunch, like electricians, you'd eat your lunch, probably out on the job or if you're in the shop, you sat on the bench and ate your lunch and you could go to probably a sink. They had them and wash your hands. And then the lead furnace, they'd just go sit down, take a sandwich, hold it up like this and eat it all except the part they were holding with, with lead on their fingers.

Howie Smith [00:07:55] Were there very many accidents in those days?

Ed Provost [00:08:00] Not too many, no. No, most of them would be some burns. See, when they'd wheel the slag or the metals in pots, through pots with wheels on them, the men would pull them out if it was raining and they'd spill any of that, why when that hit the, what is it, the splatter and probably some of it would fly and hit them in the face or on the hands or something like that.

Unidentified [00:08:41] There's no safety equipment?

Ed Provost [00:08:43] Not very much. No.

Howie Smith [00:08:48] They didn't have any protective clothing like they do now or anything like that?

Ed Provost [00:08:52] No. No. No. You had nothing.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:08:57] Things eventually improved, thanks in part to smelter manager Selwyn Blaylock, who knew that minimal improvements would boost productivity and profits. But Blaylock ruled the smelter with an iron fist. It was always his way or suffer the consequences. Ron Verzuh.

Ron Verzuh [00:09:16] Now I can talk about Selwyn Blaylock, the resident. In 1939, he became president of the CM&S Company and a great patriarch really, in a lot of ways. But let me jump back just a little bit further, really even further than the 1917 smelter strike that we're going to talk about. In 1905, maybe earlier, the first Western Federation of Miners union started at the smelter. They were following on the heels of a pretty important local, Local 38 in Rossland, the mining community above Trail that fed the smelter. And they became, I think, probably the first wobbly union, the first Industrial Workers of the World union in Canada. They were visited by his nibs, Big Bill Haywood. So that was an interesting beginning. So ten years later, not so much ten years, but seven years later, that Local 105 of WFM begins in Trail and this is a local that carries on and not very strong but they carry on you know, through the decade and they move into 1915. And at that point, mid-First World War or just at the start of it, Ginger Goodwin, Albert Ginger Goodwin, a socialist and a union organizer, is working at the smelter and he solidifies the solidarity at Local 105. And they become a force and they want to negotiate a much better agreement than they've had. Some of which was health and safety.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:11:04] We turn now to Ginger Goodwin. He took part in the great coal strike on Vancouver Island from 1912 to 1914 that we covered in an earlier podcast. Blacklisted from returning to work in the mines, Goodwin found work at Trail. In 1917, he led a strike for the eight hour day, although BC had legislated an eight hour day, it did not cover all workers, and many employers simply ignored it. Selwyn Blaylock, who was a rising star in the company, proved a tough adversary.

Ron Verzuh [00:11:40] He was a pretty vicious guy. When the 1917 strike hit, he and JJ Warren, the general manager, really did starve out the union. I mean, their intention was to starve them out and it was a winter strike, or just beginning into the winter. It didn't end until December, and the 1917 strike was I think most people would consider it a loss. I write it a little differently, but it was effectively a loss. And in fact, their own union, which had then become Mine, Mill, was really part of the loss because it failed to support them in the way it needed supporting and they basically starved them out.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:12:26] Ed Provost felt there was too much bickering among the strikers. After a few days, he decided to head to the States.

Ed Provost [00:12:34] Well, I was on the picket line the first morning, and then they had a meeting over across the river and Blaylock, he was just new as manager there because he took over from Pat Stewart just about a year, I imagine a year or so before that. And he went over there and he told them that they were out illegally because they never notified the head office or they never called for an arbitration board. And he told 'em he couldn't give them eight hours. But if they'd come back to work and notify their head office and call for an arbitration board, he would pay them time and a half for that hour from today until the day they got it. And if they didn't get it, they could go back on strike then you see, and go back legally. And of course, some of those radicals in the hall, they started hollering no, no. One of the leaders was a fellow that lived up the Gulch. He was an Italian by the name of Marshall. And then they held a meeting in the Star Theatre that afternoon and one the next day. And they were up on the stage, there were union men and non-union and some wanted to go back, others didn't. And they started fighting amongst themselves.

Unidentified [00:14:24] Well, it was a bad strike to begin with, eh?

Ed Provost [00:14:26] Yes. Because they never notified headquarters, you see.

Howie Smith [00:14:30] What was the outcome of that meeting? You said they were fighting among themselves....

Ed Provost [00:14:37] Oh, they just were going back and forth and they had a meeting the first day and the next day and a couple after. I came home, and I went and got a passport and went down to Kellogg.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:14:51] Goodwin, who led the strike, became a target for Blaylock and the company. When it was over, despite poor health, that was obvious to everyone, he was conscripted by the local draft board into the Canadian army and the killing fields in Europe in World War I. A socialist and a pacifist, instead, Goodwin lit out for his old stomping grounds of Cumberland, where he was shot dead by a special vigilante sheriff. Andrew Waldie knew Goodwin well.

Andrew Waldie [00:15:24] Now to refer to this fella, Goodwin. At that time, the miner's union office was halfway between Eaton's store and the Trail-Rossland clinic, right on Cedar Avenue. And on the corner where Kresge's is now, they operated the Meakin Hotel there, the three-storey Meakin Hotel. And I was staying there at that time and Goodwin was staying right there in that hotel. Goodwin and I had our meals together in the dining room.

Howie Smith [00:16:05] What was he like?

Andrew Waldie [00:16:07] I'm glad you mentioned that, because Goodwin was a very, very sick man. His teeth were like little pieces of barbed wire. Rusted barbed wire. He didn't have one decent tooth in his mouth. His teeth were just like rusty barbed wire. And he was a sick man. And in conversing with Mrs. Hurley later -- Mrs. Harley operated the dining room there -- and conversing with Mrs. Hurley later, she told me that he had never eaten a decent meal all the time he was there. Now, what I'm getting around to is this. That after the strike was over or previous to the end of the strike, the Conscription was invoked and everybody had to go to be examined. If they didn't enlist, they were asked to go and undergo a medical examination. I went over there with a bunch of Trail boys, over to Nelson with a bunch of Trail boys, and I was a way, way down on the list. I was classified as C-3, so there wasn't any chance at all of me going overseas. And Goodwin was exempted. Now, that's very important. Goodwin was exempted, that's very important. He was exempted because of his physical state.

Howie Smith [00:17:51] Well, you said he was sick. How was he sick?

Andrew Waldie [00:17:55] Well, he couldn't eat a decent meal, and he never ate a decent meal all the time he was in Trail there. He was sick. He's small and thin. And Goodwin was exempted. Then after the strike was all over, some of them were called up for re-examination. And Goodwin was called up. And he was passed as A-1. Rather, he passed sufficiently high to enable him to enlist and they would accept him.

Howie Smith [00:18:32] Was his health any better then?

Andrew Waldie [00:18:33] Oh, no, no. He was a sick man all the time. He was small and thin. And I don't suppose he ever ate a decent meal all the time he was here. He couldn't. Anyway, after this re-examination he was expected to enlist and he wouldn't enlist. So he beat it down to Vancouver Island. And he was hunted by the police for evading conscription. And in the fracas, I think one of the policemen was killed. I'm pretty sure one of the policemen was killed. And Goodwin subsequently was killed by another policeman. And as a fact, Blaylock today is held more or less responsible for having martyred that man by way of a grudge for having called a strike.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:19:31] With Goodwin gone and the strike broken, Blaylock then set up a company union to head off any future attempts to organize Trail smelter workers. Ron Verzuh.

Ron Verzuh [00:19:41] Nobody who worked in the smelter would ever have said Blaylock was a dummy. He knew what he was doing and he knew that he would do whatever he had to do for the company. And what he did to stop future strikes, was create the Workmen's Cooperative Committee system. The WCC. And that was basically a company union and company unions were allowed. There was no law saying they wouldn't be there, and that stayed for 25 years and kept the unions out. And it wasn't as if there weren't efforts. The One Big Union people came in and tried to do something in the '20s. You know, other people came up and just tried to organize and couldn't get anywhere, because these guys really felt that they were part of, sort of part of one big family, as Blaylock said. They didn't really think about, gee, we're being told what to do. We don't have any say. You know, and actually were dying in the workplace in some instances.

Patricia Wejr [00:20:40] But you see, the way it was organized, some people, they probably thought they did have a say because Blaylock was clever enough to organize it that way.

Ron Verzuh [00:20:49] Yeah. It's interesting, when you read the book, you hear talk, for example, from one of the presidents, Al King, and he says, Blaylock just sat at the table and they had their little meetings with the people from different plants at Cominco and, you know, elected by the people that were in the plants. And they would basically then have the meeting and then Blaylock would just say, this is what's going to happen and he slammed his gavel down and that's what would happen. Because he was funding the thing. They were coming to work and going to these committee meetings on company time and getting paid for it. So he had it pretty good there. Nobody was going to talk back to Mr. Blaylock.

Patricia Wejr [00:21:28] No. So then, except for -- yeah, maybe we could move on to, I think it was, was it 1938 that Slim Evans arrived in town?

Ron Verzuh [00:21:39] That summer and fall, yeah. That's right. Arthur Slim Evans comes to town. This guy, he's a great, great character in Canadian labour history. Anyway, he comes in, in '38, summer '38. He's assigned by the CIO to come in and organize mining and smelting workers all over the province. And if he lands Trail, with 5000 workers, that's the kingpin. He knows that. They know that. They fund him, they give him a vehicle. He drives up the Trail. He'd been there before. Slim was in the area raising money for the Spanish Civil War volunteers. So he knew what the lay of the land was. Anyway, he gets in there and kind of holds a couple of big meetings and kind of gets to know people. Slim was a great socializing guy. Like his daughter once said, you know, a pub is a pretty good place to get going on the union organizing and and Slim certainly enjoyed that part of his work. But he comes with a really interesting background and I think it came with him. Some of the workers in Trail, certainly the workers that were organizing the local, knew about his role in 1935 On To Ottawa trek. They knew that he had -- actually much earlier, they found out that he'd been at Ludlow for the Ludlow massacre and was machine gunned. And Slim had an injury for the rest of his life because of that. So he came with some pretty hefty credentials and that stood him in good stead for a while. But afraid he got himself into some trouble pretty early on, and he basically had to leave town. He got into a kerfuffle with the police and with courts. And, of course, he had all sorts of enemies already because they didn't want a union. This guy was evil. You know, everybody was against him. So he had to leave and another fellow took over. And these guys were very, very strong Communists. And their philosophy was communist. And they brought a local flavour to it. And I didn't feel as I researched the book that I was talking about doctrinaire people. They actually knew where they were. They knew what the workers were about. They were using their political ideologies to try and forward the workers betterment in Trail, not necessarily, you know, in Toronto. So that was kind of a neat facet of this organizing drive, was they were Communists and there were others that we can talk about that came forward, and they had this local sense of rightness, of justice. And that was Slim's guidance. Slim injected that. And then along came other people. Gar Belanger became the first president of the local when Slim was there. And he has a story to tell about Slim, too. But he he was a strong Communist and his wife, Tilly Belanger, was an equally strong Communist. And they led the way all the way through the period I'm studying and wrote about. Quite interesting characters. Try to find something out about them. You can't even get an access to information request to get their names up, never mind their backgrounds.

Patricia Wejr [00:24:51] Interesting.

Ron Verzuh [00:24:54] Finally they ran for Parliament in 1953. Interesting characters.

Patricia Wejr [00:24:58] Yeah, but as you described in the book, the next 20 years were just basically pretty unbelievable, weren't they? And the tensions, the world wide anti-communist campaign and all impacting Trail. But, you know, they they kept trying and...

Ron Verzuh [00:25:25] It's interesting too because those six years from the beginning when Slim comes to town and the final year, 1944, those six years were battleground. They were fighting tooth and nail all the time. You know, they knew everybody was against them and they were facing real, you know, a real difficult period. And, you know, it was families against families and workers against workers in the plants. And as we talked about it, there was the company union that was still striving. Now, the company union part ended in, I think it was '43 with the laws changed. They changed the law that year, the provincial law I mean, and they then banned company unions. And that meant the end of the Workmen's Cooperative Committee. And of course, then the following year, another Communist, Harvey Murphy, rolls into town from the Mine Mill office in Vancouver, and he kind of runs the last victory lap in a sense as an organizer. But I find it interesting because a lot of the stuff that happened in those years, we've talked about the strike, the beginning of the union, I argue that those kind of things gestated over the years and decades and that the people that organized the union and also the people who joined the union, had a kind of a historic sense of who they were and the battles that had gone before them. I mean, maybe it sounds a little, you know, maybe not. But I think there's enough evidence to suggest that they and their fathers and grandfathers passed on those kinds of feelings about why we need a say in our workplace, you know. So those things kind of came to a head in '44. The the federal government passed a law that basically allowed unions to organize and, you know, I don't know if they permitted strikes, but I forget now what it was. It was a Privy Council order, Order in Council 10-03 and that kind of broke the back there because we hadn't had that in Canada. The US had had something called the Wagner Act since 1935, but this was kind of our Wagner Act in the sense that it allowed organizing and it allowed workers to get organized into a union. And after that, Blaylock. Well, we should end it with Blaylock really, in a sense, because he died the next year.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:27:52] Thanks to their new legal clout, Local 480 of Harvey Murphy's Mine Mill and Smelter Workers Union was finally able to sign their first collective agreement in 1944.

Ron Verzuh [00:28:06] As I say, Blaylock died in '45, in the fall. But another guy came along and he was working -- Murphy had hired this guy to be an organizer around the area, and he did some organizing. His name was Clare Billingsley. Clare decided that he had had enough of the "commies", and he had decided he would run for the presidency of Local 480. And he did so. And he won. Murphy, I'm sure, was crying in his beer, about that, or his whisky. But he won and then he led the independent group toward really desolation. Because they were still a union, they were still officially certified by the Labour Board, but they were being undermined by this group that was slowly spending whatever money they had. If they had a war chest, it was all sifting out. And by '47, with the arrival of the Taft-Hartley Act in the United States, which was a very anti-union act, kind of undoing the Wagner Act of ten years before, came in. And it had an effect on Canadian workers because a lot of these unions were American based. So Billingsley guided the group basically to resign. So the executive gave it up. And he then was obviously working behind the scenes to an extent, to get the United Steelworkers of America to come in and take over, to basically decimate Local 480 because it was a Mine Mill local, and they were led by Communists and this was not on at that time, kind of an early second red scare period. That was, again, another big war, another big smelter war, to try and keep the the local union under Mine Mill control. And of course, this was happening all over North America. So the book tries to talk about other locals and other unions in different parts of the States and Canada who were fighting these raids constantly. In Trail, they somehow miraculously pulled it off.

Music: 'Ode to the Smeltermen' performed by Jeff Burrows [00:30:21] Ye union smeltermen of Trail to you I sing tonight. It gives me pleasure, joy and pride to aid your cause of right. A workman's course is full of woe in every sphere of life. Yet all should work harmoniously, avoiding serious strife. So smoke and drink like brothers here, let not your minds prevoke. And practise strict equality while you toil in smelter smoke.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:31:04] Meanwhile, there had been World War II and the extraordinary entry of women into the industrial workforce. They replaced the men who had left their jobs to fight fascism overseas. The smelter was no exception. Blaylock began to hire women in July of 1942. They became members of Local 480 when Mine Mill was certified in 1944. However, that did not protect them when the war ended and the men returned from Europe to reclaim their old jobs. As in all industrial workplaces that hired women during the war, they were simply let go. But it was a profound workplace experience for the women.

Ron Verzuh [00:31:47] It was a really interesting chapter for me. Partly it was about the women war workers who took the jobs the smelter worker soldiers had left, the enlisted guys. And partly it was a sort of a story of what the work was like and how the women actually were, and at the end of the day, most people had to agree that women are doing a better job anyway and they were working in these dirty, filthy plants, right. And they were doing it with a lot of aplomb, a lot of spirit. So you see the pictures of those days and you see that spirit coming out, you know, with the women in their coveralls and so forth. It was actually a really interesting opening to explore kind of second stage feminism, if you will, because this was giving women power. They weren't getting paid as much. They were only getting paid 80% of the salary men would get for the same work. But this was a moment where they could see some sense that they could see some leadership power here. The union wasn't so cooperative. Now they have in their -- Mine Mill had a very progressive constitution. They did respect everybody, on paper. But you've got a lot of guys who were still subscribing to what was called the breadwinner tradition, the male breadwinner tradition. And the women that were active at that point knew they were going to be facing that. During the same period -- these hearings took place around 1942. So Blaylock was hiring women quite frequently, all the way up to '45. But there was also an active movement to create a Mine Mill -- they called them Ladies Auxiliary, Women's Auxiliary. And they became very active in supporting Local 480 during the raiding years that we discussed, the steel raiding years. And they were incredible. They did radio broadcasts. They circulated leaflets. They were writing articles for Union, the paper that was produced out of Colorado where Mine Mill was based. I mean, they were really just very active and they ran into some really interesting stuff. It's covered in that chapter, it was just an exciting period. And when the men came back from war and took over those jobs, I think it fizzled a little bit. But, you know, into the '50s, the Auxiliary is still working hard. And it's an interesting thing, too, because scholars of the women's movement know this, that this wasn't a group of people who just, you know, cooked soup in the back room and put it on the table for the hard working men, you know, or the strikers or whatever it was, because there weren't any strikes then. But these were people who were active players. They were active political players. Some of them were Communists, some of them were just active, knowing what's going on, people, you know. And that sort of a moment that I think got lost after the war ended and the Cold War took over and that feminism didn't revive again, I don't think really until the '60s.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:34:55] As Ron describes in 'Smelter Wars' one of the women's broadcasts was entitled "How Disruption of Our Union Affects the Women Folk". They advised the Steelworkers to keep away from Mine Mill, but it took a lot to deter Steel, who continued their raiding efforts for many years, fuelled by the anti-communism many mainstream unions embraced.

Ron Verzuh [00:35:19] There were things that were happening in the early Cold War era that fascinated me, how our little local union was fighting against McCarthyism, right? They were fighting for whatever sense of democracy they knew about. And by '55, the Mine Mill was kind of on the on the skids, or going toward the skids, it was still around. And they decided to create a Canadian Mine Mill. And they had a convention in Rossland just next door to Trail. And they created a new union, a national union, and Harvey Murphy and a few others, Al King and a few of the stalwarts at Local 480, moved over to that. And Harvey became -- there's so much about Harvey that I haven't said, because I'm in the process of writing a biography of him right now. But he went off and became the editor of the Mine Mill Herald and was vice-president of the new Mine Mill in Canada and still continued to bargain for Trail, you know, in those late years after '55. But essentially the game was up. The new union lasted for another ten years, but it wasn't likely to go much further. There wasn't anywhere for it to go, eh? I think the other thing that was interesting to me was the changes -- there were some political changes afoot. There was a big NDP convention in '56 or CCF convention in 1956, which changed the ideology a little bit. And as you know, there's a chapter in the book on that discussion, ideological battleground. But it was also in '56 where I think the two big unions, the CCL and this TLC.

Patricia Wejr [00:37:10] Yes, merged.

Ron Verzuh [00:37:12] As they did in the US with the AFL-CIO. Those two unions, those two central bodies merged. And there was some hope that Mine Mill would get out from under the red taint and be a legitimate affiliate. They battled all the way through that period. Their leaders were taken to court. Their big sin was that they were Communists. So that was kind of where I thought the book should end rather than me carrying it on for another ten years, into more raids and, you know, more battles.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:37:45] But the Steelworkers were never able to take control of Local 480 from Mine Mill. Despite all the red-baiting, its non-Communist members stayed true to the union that had fought on their behalf for so many years. But as Ron mentioned, Mine Mill saw the writing on the wall, and in 1967, Harvey Murphy negotiated a merger with the Steelworkers and recommended Local 480 members accept it. Many were bitter about the deal.

Music: 'Ode to the Smeltermen' performed by Jeff Burrows [00:38:14] With unity and stable mines, the workman should progress. And arbitrate all grievances which leads to sure success. Be loyal to your order. To each brother, lend a hand. Like true men strive to aid and cement the Federation band. So smoke and drink like brothers here, let not your minds provoke. And practice strict equality while you toil in smelter smoke.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:39:03] 65 years after its demise, the Mine Mill and Smelter Workers Union retains a legendary status as the most successful of all the Communist led unions that organized much of Canada's industrial workforce in the 1940s. We are indebted to Ron Verzuh for his book on the fascinating history of Mine Mill at the huge smelter in Trail. It's a great story and as you have just heard, Ron tells it well. 'Smelter Wars' is published by the University of Toronto Press. That wraps up another edition of On the Line. We hope you've enjoyed it. And if you've never been to Trail, put it on your bucket list. Looking down the main street with the smelter perched high above on a steep escarpment is one of the most dramatic sights in British Columbia. Thanks to my highly esteemed colleagues, Patricia Wejr, who shaped the podcast and interviewed Ron Verzuh. 'Ode to the Union Smeltermen' was performed by Jeff Burrows. The interviews with the veteran smelter workers were conducted by Howie Smith. I'm your host, Rod Mickleburgh. We'll see you next time, On the Line.

Theme musid: 'Hold the Fort" [00:40:19]