On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

Episode 14: The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters

As Black History Month comes to a close, On the Line marks the occasion with a fascinating look back at the history of train sleeping car porters, almost all of whom were Black. It's a story that has only recently started to be told, and combines the history of Black employment in Canada, unionization and the fight for dignity and equality.

We examine those long lost days mostly through the voice of Warren Williams, whose Uncle Lee was in the forefront of the drive to organize Sleeping Car Porters in Canada. Warren is the current President of CUPE Local 15 (Vancouver), one of the biggest CUPE locals in Canada.

Listen to Warren's full interview here: https://vimeo.com/793211236

FEATURED MUSIC: Theme song: "Hold the Fort" - Arranged & Performed by Tom Hawken & his band, 1992. Part of the "On to Ottawa" film produced by Sara Diamond.

"Too Too Train Blues" - Performed by Big Bill Broozy

"Midnight Train" - Performed by Oscar Peterson

RESEARCH: Research and script for this episode by Patricia Wejr & Rod Mickleburgh. Our thanks to Warren Williams for sharing his family's story as part of the BC Labour Heritage Centre Oral History Project in Feb. 2021, an interview which the clips in this episode are featured from.

Learn more:

https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/frank-collins-union-leader-black-activist-1940s-vancouver/

Travis Tomchuk. Black sleeping car porters: The struggle for Black labour rights on Canada’s railways. Retrieved from https://humanrights.ca/story/sleeping-car-porters

- Follow us https://www.facebook.com/LabourHistoryInBC/

- Browse https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/

- Find us on Bluesky https://bsky.app/profile/bclhc.bsky.social

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bc_lhc/

- Send your feedback info@labourheritagecentre.ca

- Thanks for listening!

Rod Mickleburgh [00:00:11] Welcome to another edition of On the Line, a podcast that focuses on British Columbia's rich labour heritage. I'm your host, Rod Mickleburgh. February is Black History Month in Canada. On the Line has marked the occasion this year with a look back at the fascinating history of sleeping car porters, almost all of whom were Black. They were essential during the heyday of overnight train travel. It's a story that has only recently started to be told. Combining the history of Black employment in Canada, unionization and the fight for dignity and equality on the rails. Kudos to the CBC for its current series on sleeping car porters, called simply, The Porter. Recommended. We examine those long ago days, mostly through the voice of Warren Williams, whose uncle, Lee Williams, was in the forefront of the drive to organize the sleeping car porters. Warren is currently president of CUPE Local 15, representing inside workers at the City of Vancouver. But in the early 1980s, he worked for the railways, including a short time as a sleeping car porter himself. By then, thanks to his Uncle Lee and other porters who stood up to the railway companies, much had changed for Blacks on the rails. What follows are excerpts from an interview I did with Warren Williams last year. Warren talked about the history of sleeping car porters in Canada and his family's experience on the rails, beginning with his own time working on the railroad.

Music: 'Too Too Train Blues' performed by Big Bill Broozy [00:02:14] Oh baby, I hear that whistle blow. Oh baby, I hear that whistle blow. That she blows just like she ain't gonna blow no more....

Warren Williams [00:02:40] But by that time, you had Blacks working, as I said myself, as a dining car steward was unheard of back in my uncle's day and my grandfather's day. And so you had Blacks working as dining car stewards and as service managers and sleeping car conductors. Still didn't have any Blacks working as train conductors or brakemen, or not that I know of, or engineers or firemen. That was still predominantly held by whites. There were a couple of Indigenous fellows doing that work in northern BC. But yeah, my grandfather, interestingly enough, was very upset when I hired on with the railway. When he found out that I had hired on with the railway, he was not happy about it at all. At the time, you know, they had dealt with a lot of racism, etc., and he made it quite clear that that's not something he wanted his grandsons to be doing. But he said there's nothing I can do about it now you've signed on. I'm just going to tell you how to take care of yourself in close quarters. And that's the truth. He did that. And be careful and do your job to the best of your abilities and you'll be doing it better than most and they'll have no reason to come after you. But they will come after you. Yeah.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:04:01] Warren's ancestors, on both his father and mother's side, fled the racism of the United States to settle in rural Saskatchewan. A church built by his mother's family still stands and is now a heritage site.

Warren Williams [00:04:16] And the Saskatchewan government just recently, in the last ten years or so, designated the church, that's a log-hewn church built by who they called the Shiloh people, by my descendents, my great grandfather, Ceasar Lane, built the church and they've just designated it a heritage site. And so they're still out there. And my ancestors, some of my ancestors are buried there in the church. There's a plaque there and that's my family. Yeah, it's pretty cool.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:04:55] So what did they do in, was it Hillside?

Warren Williams [00:04:58] Yeah, Hillside. They were farmers. They came up with farming. I believe at the time the government was --it's interesting -- the government was offering in Canada, it was 60 acres and a mule I think it was. In the United States, it was 40 acres. And you've probably seen the logo right. So that's, you know, they were trying to -- of course, this is during Jim Crow era in the United States, and so a lot of Blacks were migrating north to Canada. And it got to the point that the Canadian government in 1911, put a ban on Blacks migrating, immigrating. They did it for a year, yeah, apparently for a year.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:05:38] That had an impact on Warren's family. They had to move in search of work. That brought them to the railroad.

Warren Williams [00:05:46] Because, of course, it was hard for Blacks to get work, right. And so the families eventually either moved east to Winnipeg or west to Alberta. And like my Uncle Lee, for instance, his first -- he got a job in South Battleford and that's where he got his first job with the CNR. And then the family migrated to Winnipeg, just like a lot of Black families did. The railway was the hub for Canada at the time. And Winnipeg was central to all of Canada at the time. And so everything basically, everything went through Winnipeg at one time.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:06:26] Yeah, both rail lines.

Warren Williams [00:06:28] And both rail lines. Exactly. Went through Winnipeg too, CPR, Canadian Pacific Railway and Canadian National Railway. And so my grandfather, Carl Williams, and his brothers, Lee Williams and Chester and all that, they migrated to Winnipeg and started working on the railway. My grandfather and a couple of his brothers, Tommy and Roy, worked on for CP Rail and my Uncle Lee worked on Canadian National Railways. And at that time it was Canadian Blacks from, you know, that had migrated from the United States and or were born here, worked on the railway, and then you started getting an influx of Caribbean peoples. Black people from Caribbean. From the West Indies, Jamaica and Nova Scotia started to come to Winnipeg and migrated to Winnipeg for work.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:07:27] They hired on as porters for the railways' sleeping cars.

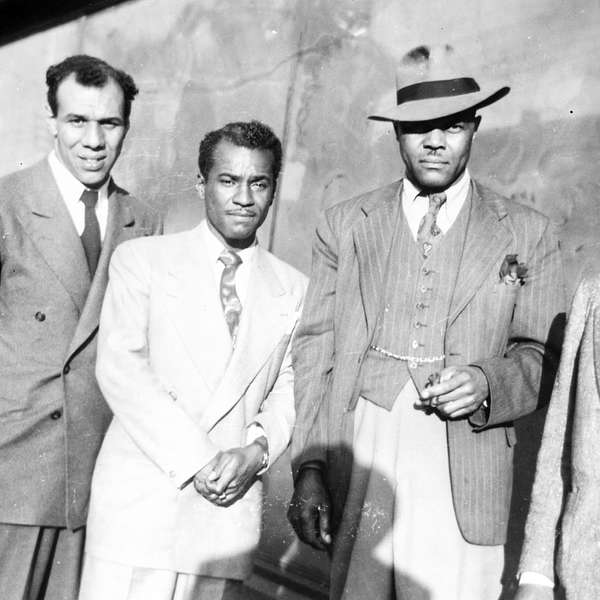

Warren Williams [00:07:31] They were all sleeping car porters. My grandfather was a -- he had a trade. He was a stuckler. You might remember what stuckle is. Like my grandfather did that type of work on the side, but he couldn't get work. He was very good at it and when he did get work, people would watch him work and apparently he was that good at it and famous, that was the thing.. But he just couldn't maintain work because they weren't hiring Blacks in Winnipeg. And the only place that he could get hired was on the railway. And that's what happened with a lot of the Blacks. And it was, you know, in the community, it was a good paying job. You know, it was steady work, wasn't good-paying, but it was steady work, money coming into the family. You could raise a family on it. And you had a bit of prestige in the community. I don't think I've ever seen any of my uncles or my grandfather at any time not wearing a suit except if they were in the house. When they went out, they were in a suit, jacket, tie and off they'd go. And that's how they would go to work and that's how they presented themselves at work.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:08:37] The tradition of Black sleeping car porters had begun in the 19th century when George Pullman invented the pull-out berth. Pullman wanted Blacks to make up the berths and cater to overnight travellers because he considered the job akin to domestic service. Canada's two main railway companies, Canadian National and Canadian Pacific, maintained the tradition in an age rife with discrimination. As Warren mentioned, work on the trains was one of the few jobs Blacks could get was steady wages. Daniel Peterson, father of famed Canadian jazz pianist Oscar Peterson, was a sleeping car porter. So it may have been no coincidence that the song most associated with Oscar Peterson was the classic jazz tune 'Night Train'. But it was far from a dream job. Porters were on call too sleeping car passengers around the clock. In addition to making up and then re-converting their berths in the morning, they carried and stowed their luggage, pressed their clothes, shined their shoes for a tip, if they were lucky, served them food and drinks and did anything else a passenger might want. They had to provide their own uniforms and they had no job security. If a passenger complained, they could be fired, just like that. As if all that wasn't enough, shifts typically lasted three days, yet there was no fixed place for them to sleep.

Warren Williams [00:10:22] You very rarely, back in those days, up until 1940, you didn't even have a berth. And then after 1940, you may get a berth if there is room. But even if there was room prior to 1940, you didn't get a berth. And what they had on each car was called a jump seat and it was about just wide enough for you to sit on. And they called it a jump seat because the bell would ring and you'd look up on the board and you'd see, okay, I had to go to this room so you jump up. And then that seat, that was on a hinge, and it would fold, jump back up into the wall, right. So basically, you slept in that seat basically... You didn't have the dignity of having a place to sleep. And of course, you know, like you're cleaning up people's messes 24/7. Yeah. Any time of day or night at their beck and call, absolutely. And you better be polite. You better be courteous. You better be smiling. You better not give them any reason to be upset because you could, you know, they would write you up. And if you received sixty demerits, you'd be fired. There's no ifs, ands or buts about it. And if you became, what was called in the day, too familiar or too friendly with white female passengers, that was pretty much automatically, you're gone. Fired, right? You had to act like they weren't there, pretty much, you know, and just deal with the men. They were expected to be subservient also, right. Not only to the passengers, but to the white workers on the railway and, of course, the employer, too, right. So it was a load that they carried, but they carried it well, and were proud of the work that they did. They took great pride in the work they did, which is why my grandfather put that lesson on me, do it as best as you can, and you'll be doing it better than most. And you know... I mean, I had the experience of being asked by a passenger to shine their shoes back when I was on the railroad and I told them, no, I don't do that. And they were surprised.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:12:36] Sleeping car porters realized early on that they had to fight back against the way they were treated. In those days, the best way to do that was through a union. But when porters sought to join the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway Employees, the union proved just as racist as the railway bosses. They turned their back on the porters because they were Black. So in 1917, the Canadian porters courageously formed their own union. The Order of Sleeping Car Porters, based in Winnipeg, was the first Black labour union in North America. Two years later, despite the way they had been treated by the white Railway Union, 90 porters took part in the six week Winnipeg General Strike in 1919. Most were never hired back. [instrumental music by Oscar Peterson]

Rod Mickleburgh [00:13:41] The Canadian sleeping car porters union won some gains from Canadian National, but the CPR proved a tougher nut to crack. After 12 union activists were fired by the railway, attempts to organize porters for CPR ground to a halt. They revived in the late 1930s, when the US-based Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters expanded into Canada. After several years of secret organizing to avoid being fired, Canadian porters voted to unionize in 1942. It took three years of tough negotiations before they were finally able to sign a union contract with the CPR. The breakthrough contract gave porters a monthly salary increase, two weeks paid vacation, overtime pay, and at last, a reserved berth on each passenger car so porters actually had a guaranteed place to sleep. One more thing. Porters could now put up name plaques in their sleeping cars. No longer would they be anonymous or George, as passengers often called them. The contract was the first time a union organized by Blacks had negotiated such a detailed agreement with a Canadian company. Still on the job, discrimination remained. Black porters continued to be denied promotion. They were unable to become conductors or even work in the meal cars. Warren's uncle, Lee Williams, spearheaded the drive to end this ongoing racism. But it wasn't easy.

Warren Williams [00:15:21] My uncle in 1930 started work, yeah, 1930, started working for Canadian National Railways. And he fairly quickly found out that working conditions for Blacks on the railway were nothing to write home about and he could see the injustices of it. And initially, he would say that he tried to just do his job, not worry about it, and just come home, get up, go back to work, do his job, blah blah blah. He didn't really want to pay a whole lot of attention to it, but something along the way happened and he started to -- people in the community started talking to him and trying to push him to become part of the union. So he became chairman, I think, of the Order of Sleeping Car Porters and then went to convention because they were allowed to go to conventions. I think the first convention was in Montreal that he attended. And at that convention, he put a resolution forward to end the discrimination in their collective agreement. And it was ignored. The resolution was ignored. And so the next time he went to a convention was in Toronto and he put the same resolution forward in Toronto. And he says, you know, from what he could see from the raised house, he believed that they had the majority of votes, that the resolution would pass. But the president of the day said the resolution had failed and it didn't pass. And so then that's when he started looking at, okay, you know, what can I do? And that's when he started talking to John Diefenbaker.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:17:06] Yes. That John Diefenbaker. Prime Minister of Canada from 1957 to 1963. Diefenbaker loved taking the train to Ottawa. Lee Williams was often his porter and got to know the garrulous Saskatchewan politician.

Warren Williams [00:17:23] And then in 1955, my uncle Lee Williams, who was fortunate enough to be on a run from Winnipeg to Vancouver and he would pick up Prime Minister Diefenbaker when he was an MP and Diefenbaker would get on in Saskatchewan. And he'd ride the trains going east to Ottawa, but he'd ride the trains. And so my uncle was fortunate enough to get to know him, of course, because he rode on the sleeping car. And my uncle would be the porter, so he got to know him. And he started talking to him about the conditions on the railway and not being able to be part of this other union and the wage discrepancies and not being able to get promoted and being served food that should have actually been thrown out, that sort of thing, and the segregation of it. And so Prime Minister Diefenbaker talked to him about the Canadian -- I think I had it written down. Oh, there it is, Canadian Fair Employment Act.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:18:36] Right.

Warren Williams [00:18:37] And so he talked to him about it and then he told him what he needed to do in order to present the case, right. And so through, you know, a few trips and phone calls, finally my Uncle Lee did that in 1955 and nothing changed. And then Lester B Pearson became the prime minister ten years later, I think it was. Ten years later, Pearson was the prime minister and my Uncle Lee contacted Prime Minister Pearson at that time and told him that he expected that the law would be upheld, given the situation. And four days later, the response from the Prime Minister at that time was to tell the railway, CNR and CPR, that they would toe the line, and that's -- they became part of the same collective agreement as the white workers and were able to get promoted. My uncle was one of the first sleeping car conductors and then became an inspector, or service manager, inspector afterwards... And they became part of the Canadian union, Brotherhood of Railway Workers. And my Uncle Lee actually became president of that union shortly thereafter because the workers realized, white and black, realized that he was actually a fair individual and treated people fairly. And so he, though the white workers were the majority, he got enough of their votes to become president, you know, of the Canadian Brotherhood of Railway workers.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:20:17] Winnipeg and Montreal were the main urban hubs for the Black porters, but Vancouver was also home to many. A Black community took shape in Strathcona, close to the train stations. There was once a three story building at the corner of Main and Prior called The Porters' Club, where porters met and socialized during their downtime. Among them was Frank Collins, the eldest of four brothers in Vancouver who all worked as porters. In the 1940s, Collins was elected president of the Vancouver branch of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, a post he retained for many years. As an interesting footnote, Frank Collins was also the brother-in-law of renowned jazz singer Eleanor Collins, who recently had a Canadian stamp issued in her honour. She is still living at the age of 102. For many years, Frank Collins also headed the BC Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, underscoring the close link between the porters and the overall fight for equality for Blacks in Canada. The small but vibrant Black community in Strathcona, where the Collins brothers lived, was known as Hogan's Alley. Warren Williams said it was a real draw for porters making a stopover in Vancouver.

Warren Williams [00:21:38] That's where they all went. They all went down to Hogan's Alley. Vie's Chicken Shack was down at Hogan's Alley so they would they would go to Vie's and they would eat at Vie's. It wasn't until the late '60s, early '70s, that they even actually were put up in hotels to sleep. They actually stayed -- they actually had sleeping cars on at the rail yard.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:22:02] At the sidings.

Warren Williams [00:22:02] Yeah, where they slept, right. But yeah, they would go to Vie's and Hogan's Alley and and they would go to The Cave. The Cave downtown was one of the hubs for Black American and Canadian talent and jazz and blues and rhythm and blues. And, you know, Marvin Gaye was there. The Supremes were there. What happened, when I was probably 14, my Uncle Lee was a deacon in our church, Pilgrim Baptist, in Winnipeg. And the church formed a youth group and youth services. And through that, my Uncle Lee and my grandfather and other uncles that worked on the railway at the time, were able to get us all passes, you know, use the family pass and took us all to Vancouver, took about 30 kids to Vancouver. And part of that trip was to go to Hogan's Alley. This is the Black community in Vancouver. And we went to Vie's Chicken Shack and it was a great experience, actually. It was a great experience. Yeah. One of the things about being Black in Canada, is now we're so dispersed, you know. Like we don't have the same sense of community that I grew up with. But even with a sense of community that I grew up with in Winnipeg, I took the train, when I was 16, to Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. And of course, Nova Scotia is where the greatest majority of Blacks are and were. And it was, even for me, it was an eye opener, but it was like being in heaven.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:23:52] Lee Williams left a legacy few can match. In 2002, at the age of 94, he received an honorary doctorate from York University in Toronto in recognition of his lifelong commitment to the battle for racial equality. Warren Williams looks back on his Uncle Lee with real pride.

Warren Williams [00:24:13] Well, I think that what he really showed people is, you know, he was the first of many -- he died in 2004. And throughout his life, he would say and he believed that we're equal and people should be treated as equals and people should be treated with respect. And I think that's one of the legacies. And the other is, you don't have to settle, like you don't have to settle, if you're willing to work for it, you can achieve. But it doesn't -- it's not just going to be handed to you. So if you're expecting it to be handed to you, it's not going to happen. But if you're willing to work for it [unclear] I think that's the big one. And I think that for a lot of our family, especially my age group and maybe, you know, 15 years younger, my younger cousins, they all learned that. They all learned that if you're willing to -- if something is important to you, and you're willing to step up for it, you can make it happen.

Rod Mickleburgh [00:25:17] Thanks to Warren Williams for adding his take on the history of one of Canada's most interesting unions, which is only now becoming better known. If you'd like to learn more about Canada's sleeping car porters, may I recommend the comprehensive account by Cecil Foster and his book, 'They Call Me George: The Untold Story of the Black Train Porters'. And thanks as well to my hardworking podcast colleagues Bailey Garden and Patricia Wejr. I'm your host, Rod Mickleburgh. We'll see you next time, On the Line.