On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

On the Line: Stories of BC Workers

Episode 5: The 1921 New Westminster Teachers' Strike

In this episode, we look back one hundred years to Valentine's Day, 1921. On that traditional day of romance, a group of courageous public school teachers in New Westminster, BC did the unthinkable: they went on strike. Their walkout had a lasting, positive impact on teachers across the province for years to come. There would not be another strike by a teachers local in the province for 53 years. This is their story.

What led these teachers, most of them young women, to take their bold action was a familiar situation that continued to plague teachers for decades - a stubborn local school board, the right to arbitration, and recognition of their union.

Learn more: https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/bctf

FEATURED MUSIC:

Theme song: "Hold the Fort" - Arranged & Performed by Tom Hawken & his band, 1992. Part of the "On to Ottawa" film produced by Sara Diamond.

"Lament for Education" - Written by Christina Schut, 2002.

"As Long As It Takes" - Written by Geoff Peters and Marion Runcie, October 2005.

The songs in this episode were performed by a group of BCTF activists called More Than Just Pay performed a sampling of teacher "protest" or "folk" songs from major BCTF campaigns starting in the 1970s. The songs were created by teachers to inform, educate, motivate and entertain. Used with permission of Geoff Peters. Part of the BCTF Online Museum's "History in Song" collection. bctf.ca/history/

VOICEOVER:

"William Plaxton" - Wayne Axford

INTERVIEWS

Ken Novakowski, past President of the BC Teachers' Federation & retired chair, BC Labour Heritage Centre

Sarah Wethered, President, New Westminster Teachers' Union & BC Labour Heritage Centre volunteer

Interviews done by Patricia Wejr on behalf of On the Line, 2021.

RESEARCH:

Research and script for this episode by Patricia Wejr & Rod Mickleburgh.

BC Federationist February 21, 1921

BC Labour Heritage Centre pamphlet by Nicol, Janet New Westminster teachers deliver a special Valentine almost a century ago

Norman, Steve The New Westminster Strike of 1921 The BC Teacher Jan-Feb 1984

Novakowski, Ken and Wethered, Sarah Jan-Feb 2021 Teacher Magazine New Westminster teachers make BCTF history – 100 years ago

Vancouver Sun, February 1921

- Follow us https://www.facebook.com/LabourHistoryInBC/

- Browse https://www.labourheritagecentre.ca/

- Find us on Bluesky https://bsky.app/profile/bclhc.bsky.social

- Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/bc_lhc/

- Send your feedback info@labourheritagecentre.ca

- Thanks for listening!

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:00:19] Welcome to another edition of On the Line, a monthly podcast that aims to shine a light on British Columbia's rich labour heritage. I'm your host, Rod Mickleburgh. In this episode, we look back 100 years to Valentine's Day, 1921. On that traditional day of romance, a group of courageous public school teachers in New Westminster did the unthinkable. They went on strike. Their walkout had a lasting, positive impact on teachers across the province for years to come. There would not be another strike by a teachers local in BC for 53 years. This is their story.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:01:06] What led these 88 teachers, most of them young women, to take their bold action. It was a situation that plagued teachers for decades: a stubborn local school board. What they wanted was straightforward, the right to arbitration to settle their salary demands, a right that was guaranteed by provincial legislation, and recognition of their union, the New Westminster Teachers Association. But the school board refused to even consider either of these demands. Its hard-nosed chair, TJ Trapp, could be speaking for many penny-pinching local governments today when he declared the board has gone to its limit in this case and do not feel justified in saddling the citizens with heavier tax obligations. William T Plaxton, secretary of the teachers association, responded to the board in kind.

Wayne Axford voicing William T Plaxton's letter: [00:02:08] Dear Sir, at a meeting of this Association this afternoon, the teachers, after full and calm deliberation upon receipt of the Board's letter refusing further negotiations, unanimously decided that unless the Board meets the Executive of the Association with regards to the salaries for this year, the teachers will not be in school on Monday.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:02:33] When the Board refused once again to meet with the teachers, they made good on their threat to strike. It was not an easy decision. More than 3,000 students were enrolled in New Westminster's seven primary and two secondary schools, and the teachers could not be sure how the community would react. But there was too much at stake to back down. The strike was on. As the day went on, perhaps they were rallied by song, as teachers have been in much later strikes.

Music performed by More Than Just Pay [00:03:06] And the principal rubbed his hands in glee, a bluff that made the government see that ther teachers have to listen to me because I've got all the power. Power, power. The teachers have to listen to me, because I've got all the power. Superintendent nodded his head, assembled his management team and said those teachers have really lost their cred and we've got back our power, power, power. Those teachers have really lost their cred and we've got back our power. The teacher quietly closed her door, she said, I won't do anything more...

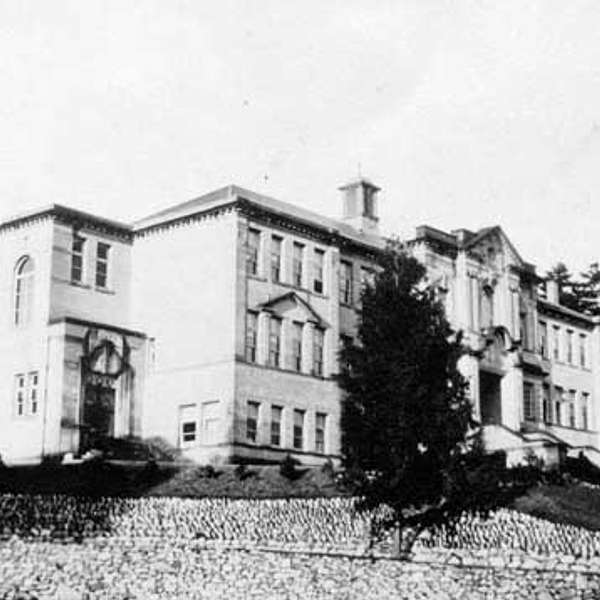

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:03:57] That morning at the Duke of Connaught High School, principal RA Little called several hundred students together and told them there would be no classes until the school board met the teacher's demands. The students erupted in cheers. Equally sympathetic principals at other schools also sent their students home. The strike prompted a banner headline on the front page of the Vancouver Sun: Teachers Strike in Royal City. Margaret Brunette was seven years old when the strike began. Her father was one of the striking teachers. Ninety-six and a half years later, at the age of 104, speaking at the unveiling of a BC Labour Heritage plaque to commemorate the strike, she recalled what it had been like for her family.

Margaret Brunette: [00:04:49] Well, the things that one remembers and the things that you don't remember are very astonishing. But vivid in my memory is the strike of the teachers in New Westminster. When we went to New Westminster, it was just immediately before the strike. Now, we had been welcomed in the ordinary way that a neighbourhood would be welcoming a new family. But when they heard that Dad was a striker and a part of the organization of the strike and proud of it, we were just rejected. It wasn't something that any civilized woman or man would participate in.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:05:37] Luckily, that hostile response was not typical. It likely reflected the more upscale neighbourhood where her family resided. By and large, community support for the teachers was strong, from the municipal council to parents to the students themselves, many of whom took part in a march to let the school board know they were behind the teachers 100 per cent. Ken Novakowski has researched the New Westminster teachers strike. In a recent interview with Patricia Wejr of the BC Labour Heritage Centre, the former president of the BC Teachers Federation paid tribute to the teachers pioneering action.

Ken Novakowski: [00:06:20] Well, it had been only the second strike that teachers had undertaken in British Columbia—the BC Teachers Federation came together in 1917 and in 1919 Victoria teachers had struck. Up until that time, there was no teacher involvement in the setting of salaries or anything in terms of the way they carried on in school. And in 1919, Victoria teachers through a strike, managed to achieve government legislation that allowed for voluntary arbitration. In other words, both parties had to agree before you could go to arbitration. So two years later.., the New Westminster teachers were trying to get some improvements in their salaries because they had fallen behind a lot of other districts. And so they went to the school board and they wanted to go to arbitration. They were prepared to go to arbitration. It was now an option but the school board refused. And so they tried a variety of avenues of trying to persuade the board to go on to arbitration, but none of that worked. So they decided they would go on strike. You have to keep in mind, I mean, there were 88 teachers involved. The overwhelming number of them were young women. And it was really that kind of work force and they didn't have any experience in striking or taking that kind of action, whatever. Yet they went out because they felt there was no option. The board was being totally unreasonable in terms of dealing with them. And so they went out on strike.

Music performed by More Than Just Pay [00:08:05] The good news in this little town, is that it won't be very long, 'til teachers rise to right the wrong and we take back the power.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:08:30] On day two, the school board upped the ante. They warned they would send individual letters to all striking teachers, ordering them to return to work by Thursday or face dismissal. Their union told them to ignore the letters. The Vancouver Sun told its readers that it was now open warfare in New Westminster. "The entire city is agog over the crisis," the newspaper wrote. Teachers in Vancouver and elsewhere rallied to the cause. They sent telegrams of support and offered financial assistance. When the school board tried to recruit strikebreakers, the Alberta Teachers Association telegrammed the board that on no account would any teachers from Alberta be accepting a position in New Westminster. Pressure on the school board began to mount until they agreed to meet with individual representatives of the teachers. But association president JS Ford was firm. There would be no meetings until the board recognized their union. A large public meeting on Friday sealed the deal. The board capitulated. At a negotiating session the following afternoon, the board formally recognized the New Westminster Teachers Association, agreed to decide their salaries through collective bargaining, and failing agreement, to submit the matter to arbitration. The teachers returned to their classrooms on Monday morning, having scored a complete victory. They also won the arbitration that followed, bringing their salaries up to the levels in surrounding districts. But that wasn't all. Ken Novakowski said the strike had a far-reaching impact beyond the immediate settlement.

Ken Novakowski: [00:10:24] So it was groundbreaking in the sense that it was the first test of this voluntary arbitration legislation. And also it was the first time that the Association was recognized by the board as bargaining for teachers in the district. So those were significant. And one of the other side effects, just an interesting side effect, is that as a result of the New Westminster strike, the BCTF itself recognized that it had structural problems in terms of being able to provide the local with the amount of support that they wanted to. They simply couldn't do it. They didn't have the wherewithal and they needed to restructure and they did as a result of that strike. So that was significant as well. And the fourth thing I would say is, the strike itself. Teacher strikes were not very common in Canada. In fact, the Victoria strike two years earlier was the first teacher's strike in Canada. And so letters of support poured in from across Canada and money came from other locals in the province. And so the New Westminster teachers had this money, but they didn't need it after they got their award. So they gave it to the BCTF, and it became the nucleus for what we called the reserve fund. When I was active in the BCTF in the '80s, the reserve fund was a very important fund for us to be able to take political action or take some kind of action that we wanted to take, we had the money to do it through the reserve fund and that was the genesis of it. So those are four important reasons why in the history of the BCTF, those were important events. In terms of labour history overall, I think it was important because teachers were taking strike action even though there was no legislation that permitted them to do it, they were striking. And secondly, it was a union that was made up largely of women. That was not very usual either. So those were positive features. We did not have another teachers strike in a local in BC until 1974. So the Victoria and New West strikes were sort of early and important because they sort of set some cases, some ground rules. That's why we recognize them as important strikes, starting the ball rolling, which took a long time for bargaining rights, not until 1988, bargaining rights and the right to strike.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:13:05] Margaret Brunette, that seven year old who remembered the strike, went on to work for the Vancouver Public Library. But she didn't forget how her father and other teachers had to fight just to win a decent salary. And not only teachers, other workers, too.

Margaret Brunette: [00:13:22] There was no conception of the significance of the salary and of the person receiving it in those early days, but we held to our right. And so we were known to be fighters and you have to be fighters. Even today, you have to be fighters. But we had to go through these peculiar times when we weren't conceived of as human beings with a right to say who should know what we're paid, you know, that is inconceivable to me. The fight that they put up in our, not in our names formally, but in fact, they were fighting for workers. And it was tough. It was really tough. People were so arrogant. No civilized person, was the implication, would be involved in a strike, let alone a union. And all of these ugly and ignorant positions had to be dealt with. And we had to be, we had to learn. We were the product of a society that hadn't honoured its union people. And we ourselves had to learn to be proud of our work in this. And we discovered that it made the whole thing so much more important.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:15:06] It's worth noting that only two teachers showed up for work on that momentous Valentine's Day in 1921. Marjorie Mays, later Marjorie Watt, was one of those who bravely joined her colleagues on the picket line. At the BCTF's 75th anniversary annual general meeting, Jim MacFarlan introduced her to the delegates.

Jim MacFarlan: [00:15:31] On Valentine's Day 1921, that five-day strike began. One of those teachers on the membership of the roster of the Federation Local In New Westminister in 1921 was a 20-year-old woman hired as a primary teacher in January 1921. That teacher was Marjorie Mays. Marjorie is the daughter of a family who came to New Westminster in 1891. She was born on January the 28th, 1900. She attended FW Howay Elementary in New Westminster, graduated from Duke of Connaught High School, attended provincial normal school, and in 1918–1919 graduating class, the picture can be seen to this day. In September 1919, she began her teaching career at Robbins Range. The following year, she returned to New Westminister after that first year of teaching and substituted from September to December 1921. In January 21, began teaching at Lord Kelvin Elementary, where, except for a three-year break, she taught Grade One for 44 and a half years [applause] and retired in June 1965. Colleagues, it gives me a great deal of pleasure to introduce a woman who participated in one of the formative, one of the seminal events, of our early years. And she is the only person living today who was an active participant in that historic five-day 1921 strike. Our colleague Marjorie Watt.

Marjorie Watt: [00:17:33] I can't understand how we could decide to accept the little bit we got. You are really looking very fine. Fellow teachers, I am very glad to be here today. And I admit that I am very happy even with that little bit that that gave me, the pleasure with my teachers. I don't think that many of us realize after you've quit. You think, well, what have I done? I've gone there and enjoyed myself, had a good time. And here I am, left an old lady now, and nobody wants me. I love every moment of it. It's very, very nice. And I hope I can be always with the teachers by my side because I've enjoyed all the problems and everything that has come along with it.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:18:38] After she retired in 1965, Marjorie had remained active in the BCTF Retired Teachers Association.

Marjorie Watt: [00:18:46] I am very, very happy there and I think people realize that the teachers have done an awful lot for the community and we still meet every month and we still have a good speaker from all around the district there. And so we do get a little bit of being together and sharing our problems still.

Music performed by More Than Just Pay [00:19:19] We have put our books away. We're on the picket line today. BC teachers standing tall, fighting for the rights of all. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for? The schools are in despair, the Liberals just don't care. And it's four, five, six, we are taking a stand. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. We are out for students' needs to ensure they all succeed. BC teachers need a say. Please sit down with us today. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for? Our schools are in despair, the Liberals just don't care. And it's four, five, six, we are taking a stand. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. BC schools need more cash. Dip into the surplus stash. Don't just help your business friends. Attacks on us have got to end. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for? Our schools are in despair, the Liberals . . .

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:20:41] As you have heard, the legacy of the 1921 strike was felt far and wide. But what of the lasting impact in New Westminster itself? Sarah Wethered is president of the New Westminster Teachers Union. She talked with Patricia Wejr on what it meant to be part of such a storeyed local.

Sarah Wethered: [00:21:02] So I think that as I tell more and more members about this strike, that it's an event that has great pride for them or it brings out great pride for them, especially when I mention the fact that, you know, the majority of these people who were on strike were young women who made that courageous decision to to go on strike for better wages. And the fact that our long-lasting legacy was the creation of the BCTF strike fund. And for our older members that have been on strikes like myself, you know, we are still benefiting from that strike fund 100 years later.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:21:55] She said the strike was about more than the pay packet teachers received at the end of the month.

Sarah Wethered: [00:22:02] So the teachers ultimately got what they were looking for, which was, you know, a salary grid, which we still have today. You know, we do. That is the basis of all of our collective agreement today. It's how many years have you worked and what is your education level?

Patricia Wejr: [00:22:23] And before that, it was a bit arbitrary, wasn't it?

Sarah Wethered: [00:22:28] Yes, and I wouldn't have been surprised to hear that women were paid probably half of what men were paid. But today, with our salary grid, you know, men and women are paid equally. You've got ten years experience and a master's degree, it doesn't matter if you are a female or male, you will get paid the same. One of the happy jobs that I do as a Local president, and this is something that I've started as Local president, and I've been Local president since July, is every time we get a new batch of teachers hired, I go to the school board for their day of their orientation and I provide them a little gift and a welcome from the New West Teachers Union. And then I give them a little bit of history about our Local. And I always start with the teacher strike and how proud I am of the legacy of that strike for our Local as well as, as I said previously, having benefited from the BCTF strike fund, of having that strike fund being created because of our actions 100 years ago.

Music performed by More Than Just Pay [00:23:57] How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for? Our schools are in despair, the Liberals just don't care. And it's four, five six, we are taking a stand. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. We deserve full bargaining rights. We will never give up that fight. United Nations said you're wrong. We will all be standing strong. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes this time. And it's one, two, three, what are we fighting for? Our schools are in despair, the Liberals just don't care. And it's four, five, six , we are taking a stand. How long will we walk the line? As long as it takes the time.

Rod Mickleburgh: [00:24:51] In 2017, the BC Labour Heritage Centre unveiled a series of plaques commemorating the BC Teachers Federation 100th anniversary. One of them was a plaque honouring the New Westminster teachers who went out on strike all those years ago to defend their bargaining rights as workers. You can see the full collection of plaques at Labour HeritageCentre.ca/BCFT. Thanks to former BCTF president and retired chair of the BC Labour Heritage Centre, Ken Novakowski, for outlining the significance of this event as well as to local president Sarah Wethered for explaining what it meant to her members 100 years later. Both interviews were done by Patricia Wejr. BCTF member and centre volunteer Wayne Axford read the letter from Union Secretary William Plaxton. The music you heard is from the BCTF online museum's history and song collection. They were performed by a group of BCTF activists called More Than Just Pay, from a series of teachers' protest or folk songs for major BCTF campaigns starting in the 1970s. You can explore the online museum at BCTF.ca/history/. Finally, thanks again to the Labour Radio Podcast Network for including us among the 70-plus shows broadcasting and podcasting on issues relevant to working people. On behalf of the podcast team, Patricia Wejr and Bailey Garden. I'm Rod Mickleburgh. We'll see you next time, On the Line.